Call to Action:

Read more about SB22-150 on the Colorado legislature’s website, and write to your state representatives to support this important bill.

Spread the word about SB22-150 on social media using the hashtags #MMIR and #SB22150.

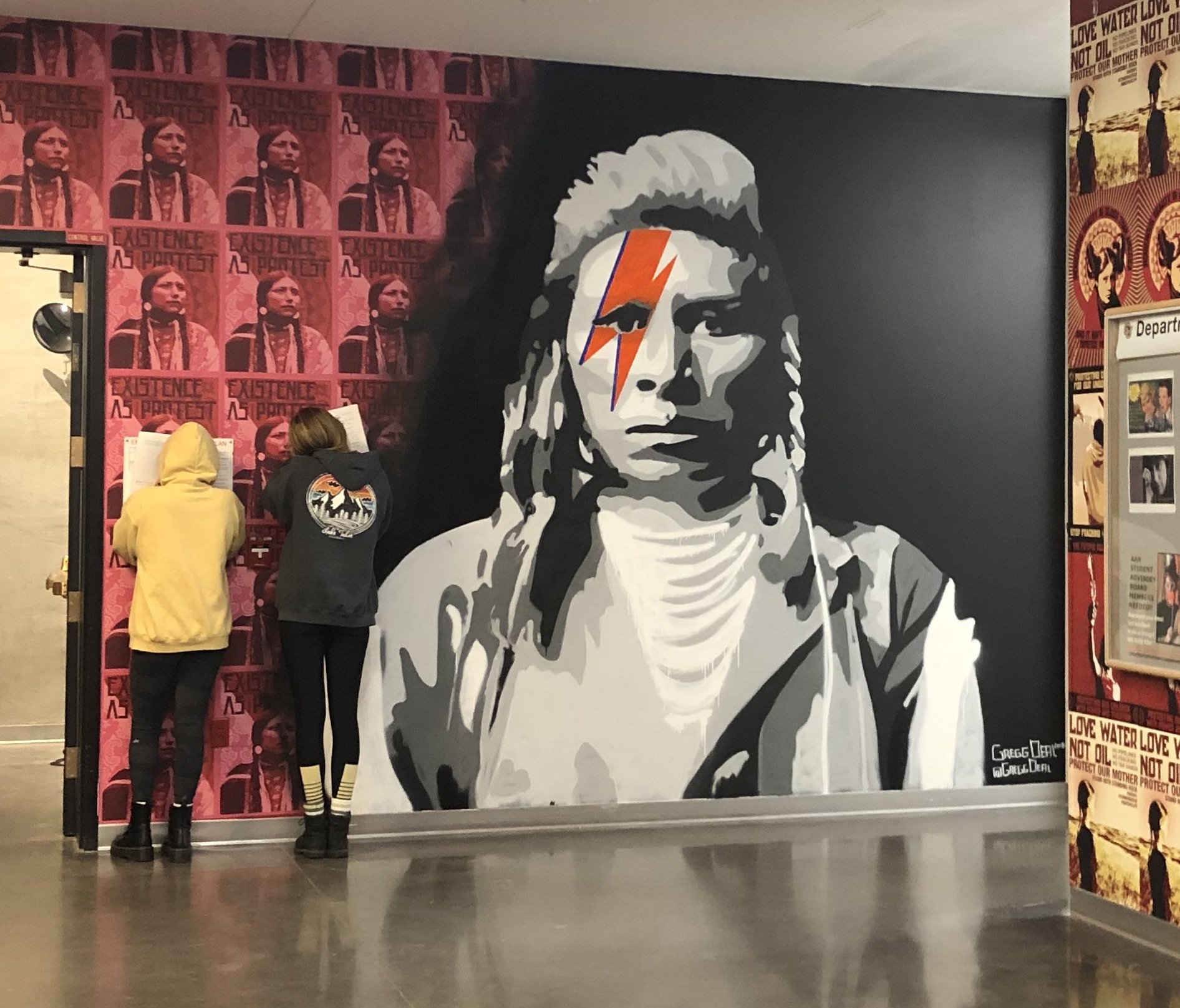

Gregg Deal: Tutse Nakoekwu (Minor Threat), a recent solo exhibition at the Emmanuel Art Gallery at the Auraria Campus, situates the namesake artist as a disruptor. Deal, a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe, often challenges Indigenous stereotypes and systems of capitalism, white supremacy, racism, and sexism with his artworks, which take the form of painting, sculpture, and performance as well as street art and muralism.

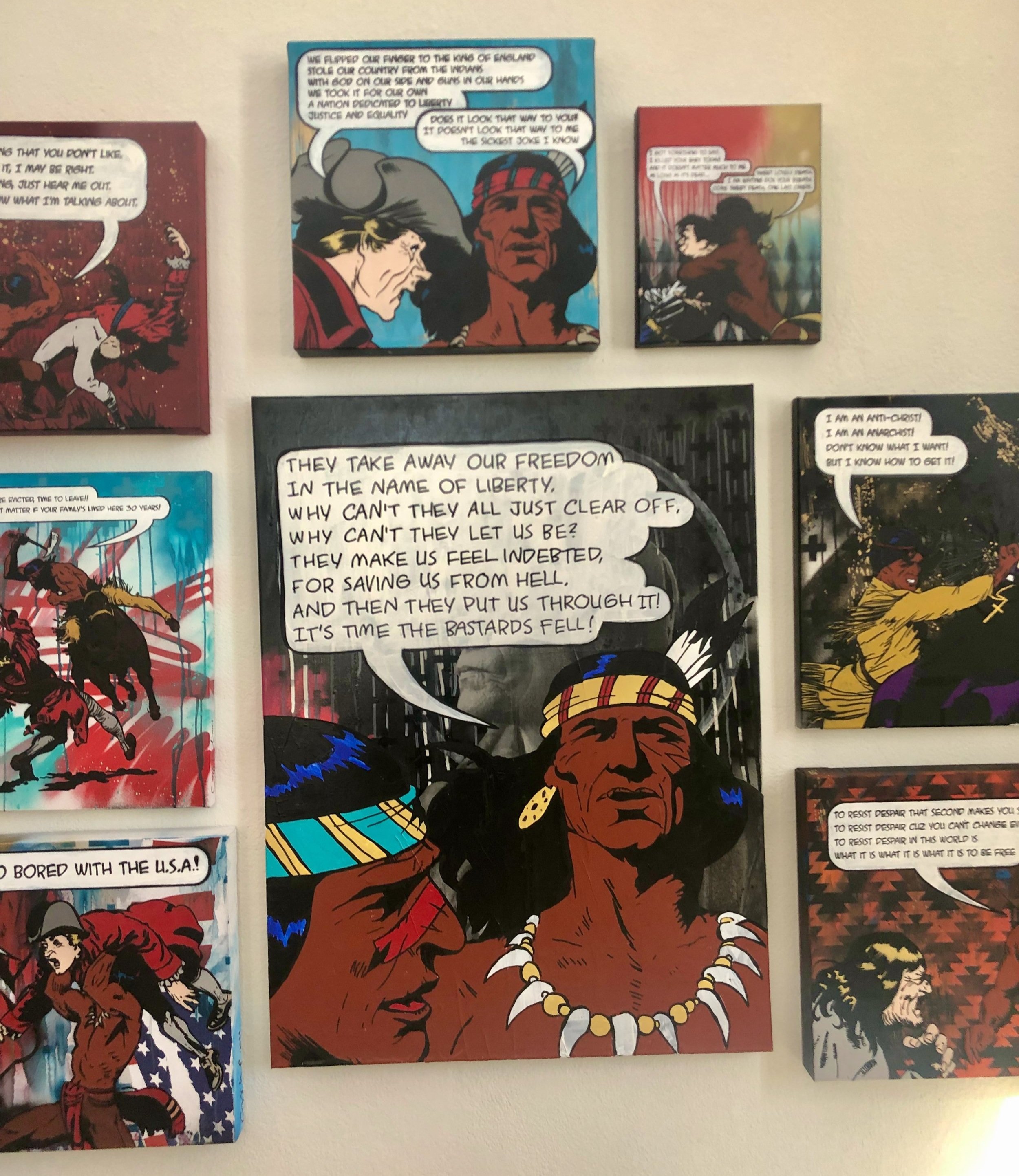

Visitors entering the gallery were immediately confronted with the variety of Deal’s art practice: the artist’s voice rings through the space as a video of his performance The Whites are Coming/ Spectator Sport played on loop; brightly-lit neon signs competed for the eye’s attention; the sculpture The Space Where Spirits Get Eaten, a towering pile of chairs referencing Indigenous boarding schools in the middle of the room, stopped the viewer short. Situated on the back wall, his series of paintings The Others, in which the artist appropriates comic book illustrations and replaces the text with Punk rock lyrics, pulled visitors further into the gallery space. Deal takes inspiration from popular culture, although often injecting such images with humor and flipping the script to force the viewer to reevaluate their assumed notions or implicit bias.

Present in Tutse Nakoekwu (Minor Threat) were a number of motifs and images that the artist regularly uses within street art practice, emphasizing his ability to move effortlessly between the gallery and the street, high art and low art, pop culture and art history. Although the exhibition’s run has ended, Deal’s prolific street art practice allows viewers to enjoy his imagery beyond the gallery walls and throughout the state of Colorado.

Indian Bowie (Ziggindigenous)

Throughout his career, Deal has utilized street art as a form of disruption. Graffiti and street art are in and of themselves an act of disruption. Graffiti writers and street artists seek to jolt passersby from their everyday ruminations through deftly placed tags, stickers, and murals. At one moment, you are making a grocery list in your head, trying to remember if you sent that email or made that doctor’s appointment, when suddenly a burst of color on the otherwise plain, gray wall of your neighborhood catches your eye. Is that an Indigenous man with Ziggy Stardust’s lightning bolt imposed on his face? Who is Deal99? For a few moments, you’re disconnected from your everyday thoughts. Maybe you pull out your phone and take a photo. Maybe you go home and search for Deal99, and suddenly you’re immersed in the artwork of and learning about the world of a contemporary Indigenous man. Would you have found yourself here otherwise?

Deal is an avid sticker designer (a number of his stickers were displayed in Tutse Nakoekwu). This particular design combines a historical photograph of an Indigenous man in traditional garb with the modern iconography of David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust. Such a combination challenges the Western viewer’s understanding of Indigeneity. In the United States especially, society frames Native Americans as relics of the past, peoples who went extinct with the buffalo and do not exist in our contemporary world. Deal’s injection of popular culture disrupts such notions and pulls Indigenous people out of the realm of the relic and into the present. “Indian Bowie” proclaims the continued existence of Native Americans in the twenty-first century and illustrates how popular culture shapes their lives.

Deal has also incorporated his Indian Bowie character into his murals. A notable example is part of a larger mural that the artist created at the University of Colorado Boulder Visual Arts Complex. The project was spearheaded by CU Upward Bound in an effort to dedicate a space to the campus’s underrepresented student population. (In 2019, less than one percent of the student body was composed of American Indian or Alaska Native students.) Deal’s mural serves as an inspiration for Indigenous students who might otherwise feel alone on campus. Indian Bowie also appears in Tutse Nakoekwu, which features a number of Untitled Hand Drums. Again, Deal fuses traditional and contemporary by painting hand drums (used by a number of Indigeous tribes in a variety of ceremonies) with images of protest and sentiments of contemporary Natives.

The Others

The Outsiders sheds light on the Indigenous experience in the U.S. Like his pop art predecessors, Deal appropriates imagery from 1940s and 1950s comic books, replacing backgrounds with his own motifs, recoloring and redrawing the imagery when necessary, and replacing the original text with lyrics from Punk rock songs (the exhibition’s title even references the Punk rock band Minor Threat). The Emmanuel Gallery’s back wall displayed more than a dozen of Deal’s easel paintings from the series in the manner of a gallery wall. The smaller size of the paintings and the collage-style format gave an intimacy to the viewing, enabling viewers to practice close looking and observe these works together. The wall stands as a comic book in and of itself, as if viewers were turning the pages of a comic in order to read the multiple scenes of conflict and violence between Indigenous characters and white colonists narrated by lyrics from Punk bands like the Misfits and Sex Pistols. Deal also pasted this imagery on skate decks displayed nearby, tying in another aspect of counterculture in the U.S.

Across the city in the River North Arts District (RiNO), viewers will find Deal’s mural The Outsiders painted for the 2019 CRUSH Walls Festival. Unlike the paintings in Tutse Nakoekwu, the sheer size and scale of the mural overwhelms the viewer. The figures stand at double life size. The weapon held by the Indigenous man on horseback feels as if it could come down on your own head. Deal chooses to reappropriate this imagery in order to refocus our attention on the power and strength of Indigenous peoples, their ability to continue to fight back and overcome in a country that views them as nonexistent. The mural’s location in RiNO also gives another layer of meaning to the DOA lyrics “YOU’RE EVICTED TIME TO LEAVE!!” as the emergence of the arts district and the mural festival have contributed to the gentrification of the area.

Take Back the Power

Another recurring image within Deal’s work is his teenager Sage. The exhibition features a portrait of them near the front door of the gallery. Sage faces the viewer with a relaxed yet focused expression, their head encircled with a halo. They wear a black The Interrupters t-shirt, another reference to Punk counterculture, and red earrings with Deal’s signature Ziggy Stardust lightning bolt. Notably, a red handprint covers Sage’s mouth. This symbol is synonymous with Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two Spirit (MMIWG2S), a grassroots movement dedicated to raising awareness and calling for response when Native women, girls, and two-spirit go missing or are murdered. Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit face oppression and violence based not only on their race, but also their gender identity. This group faces murder rates that are ten times that of the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The red handprint represents the unheard voices of the women, girls, and two-spirit who are violently taken as well as the silence of the media and the inaction of law enforcement agencies.

In 2020, the artist created a mural of this image in Colorado Springs for Art on the Streets. Deal’s mural stands at 77-feet tall (about three stories), towering over passersby. It loudly calls attention to the MMIWG2S movement, and also identifies the next generation of activists poised to continue to fight the hegemony of white supremacy, settler colonialism, and gendered violence. Sage watches over the Indigenous community in Colorado Springs, serving as a reminder of the Indigenous community’s existence and perpetual fight to guard the wellbeing and safety of Native women, girls, and two-spirit.

For the 2020 edition of Street Wise Festival, Deal created a mural that similarly features Sage. However, the mural appears darker and moodier with a stark black background and deep shadows across the teen’s face; no visible Interrupters t-shirt or Punk references. The viewer is left to contemplate the gravity of the MMIWG2S movement. His mural carries an intense sadness. In the lower right corner, Deal includes a dedication “To the lost ones. The forgotten ones. The ones without. The sad ones. The struggling ones. The ones that are alone. The ones lost in the crowd. The ones that smile through the pain. The ones who need to hear this. We remember you. We see you. We honor you. We think of you. We love you.”

On March 8, 2022, a new bill was introduced in the Colorado state legislature to create the Office of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives (MMIR). SB22-150 would grant office personnel access to state and local agency records (including criminal justice, medical, coroner, and laboratory records) relevant and necessary for the office to perform its duties. The bill would also establish a community advisory board, require the office to collaborate with the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs and other Indigenous-led organizations, and require the Colorado Bureau of Investigations to assist with cases. Importantly, SB22-150 would also create a special notification system and website regarding MMIR cases. This bill would improve the coordination, response, communication, and awareness of MMIR cases in the state of Colorado. Read more about SB22-150 on the Colorado legislature’s website, and write to your state representatives to support this important bill.

These murals are only a few examples of Gregg Deal’s expansive street art practice. Each mural functions to disrupt the urban landscape as well as stereotypical understandings of Indigenous existence. What’s your favorite Gregg Deal mural?